You’ve probably read about the legacy and low-fare ] making big “capacity cuts” throughout this year, but you may not know how those cuts will affect you. First, let’s define the term “capacity cuts.” Simply put, when an airline 1) cuts the number of daily flights on a route or 2) replaces a big plane with a smaller one, it reduces the number of available seats, and the airline thereby cuts its capacity.

What happened to airline capacity in April 2020?

The end of normal: Current airline demand – With the closure of international borders and imposition of stay-at-home directives, travel demand is almost nonexistent. In the United States alone, travel spending for 2020 is expected to decrease by around $400 billion, translating into a loss of about $900 billion in economic output.2 These numbers mean that COVID-19 would have more than seven times the impact of September 11, 2001, on travel-sector revenues.

Worldwide, airline capacity is down 70 to 80 percent in April 2020, compared to April 2019, and multiple large airlines have temporarily ceased operations. Overall, almost 60 percent of the global fleet was grounded in early April 2020.3 Again, a comparison with previous crises provides some perspective.

US airline capacity was down more than 70 percent in early April 2020, compared with April 2019 (Exhibit 1). Those drops far surpass the year-on-year declines of 19 percent after September 11 and 11 percent after the global financial crisis of 2008. Likewise, we estimate US airline load factor is now down about 70 percentage points, well above the drops seen with prior crises. We strive to provide individuals with disabilities equal access to our website. If you would like information about this content we will be happy to work with you. Please email us at: [email protected] With fleets grounded or most passenger flights cancelled, airlines are directing their energies to assisting with coronavirus-relief efforts.

Many planes that typically fly people now transport cargo, including medical supplies used to fight COVID-19. Some airlines are also providing medical workers with free round-trip flights to New York City and other hard-hit areas, while others are helping by seconding staff into areas that need extra hands, such as medical facilities and grocery stores.

These steps are a natural and much-needed first response to the crisis.

Is airport capacity a problem?

A strategic review of IATA’s Worldwide Slot Guidelines will strengthen the allocation of ever-scarcer airport capacity  Airport capacity has become a major issue as air traffic demand continues to soar. Infrastructure isn’t being built quickly enough, creating problems for passengers and cargo. There is no substitute for the physical expansion of airports to resolve this crisis.

Airport capacity has become a major issue as air traffic demand continues to soar. Infrastructure isn’t being built quickly enough, creating problems for passengers and cargo. There is no substitute for the physical expansion of airports to resolve this crisis.

- But there is a need to manage scarce capacity with a fair, neutral, and transparent system until sufficient capacity can be built.

- For that, IATA’s Worldwide Slot Guidelines (WSG) is critical.

- Despite airport capacity constraints, the WSG has enabled growth in all parts of the world.

- There were more than 2,000 new routes established at European slot-coordinated airports between 2010 and 2017, for example, enabling an extra 155 million passengers to travel.

Importantly, new entrants—including low-cost carriers (LCC)—have thrived under the WSG, According to Eurocontrol, LCC flights grew 61% between 2007 and 2016. The top airports for LCCs in Europe in terms of movements are Barcelona, Dusseldorf, London Gatwick, and Stansted—all level 3 airports (the most congested).

Similar new entrant growth is seen in other regions. “In the past five years, HKExpress has opened a dozen new routes out of Hong Kong’s essentially full airport that had no competition or only one incumbent carrier, with the effect of making all of these destinations available to far more travelers through lower fares and increased competition,” says Stephen Milstrey, Manager Network Planning and Scheduling, HKExpress.

“The historic determination guidelines in the WSG enabled this by allowing us to slowly convert generally unusable, short series of slots into valuable, full-season slots.” Full to the brim Despite the success of the WSG, there have been calls for a radical shake-up of the system and some regulators have experimented with potential alternatives.

In large part, this has been brought on by the increasing severity of the capacity crunch. In a worst-case scenario, there could be more than 300 slot-coordinated airports in 10 years’ time. Major hubs are full to the brim and the slot pool is empty. Regulators are thus concerned about how to develop the process to ensure new entrants can continue to compete.

Coupled with this is a desire to improve the monitoring of slots, so that incumbents do not abuse the WSG process. In addressing these concerns, it is critical that a global system is maintained. If the system descended into individual airports pursuing their own allocation criteria, the resulting patchwork would certainly confuse and constrict the network.

- Coordination is the key.

- A take-off slot at airport A only has value if there is a corresponding landing slot available at the other congested airport B at the right time.

- As a global industry, aviation always does better with global solutions to global problems,” says Lara Maughan, IATA’s Head of Worldwide Airport Slots.

Schedule optimization The WSG maintains value even when there is nothing left in the slot pool. Slot mobility—swapping or transferring slots to other airlines in a secondary process—allows airlines to optimize schedules to meet consumer demand with speed and agility.

- The majority of secondary slot exchanges take place for no monetary compensation as they allow the carriers involved in the exchanges to optimize their operation.

- Even at the so-called super-congested airports, airlines can eventually get access through the WSG ; Aeromexico, Air Astana, Hainan Airlines, Philippine Airlines, and Vietnam Airlines have all started operating at Heathrow in the last few years.

And once they’ve entered the market, carriers can grow, as demonstrated by HKExpress at Hong Kong International Airport. It has grown from a fleet of five aircraft to more than 20 in a short period (2013–2018). Alternatives to the WSG Many alternatives to the WSG are being proposed but each has its challenges.

- Experience continues to point the industry back to the WSG.

- Peak/off-peak pricing means airlines wanting to operate in the most congested periods pay more for using the scarce infrastructure and so it encourages airlines to use the off-peak periods—in theory.

- It doesn’t work for many reasons.

- Market demand dictates schedules, for example, not airport pricing models.

Also, airlines must utilize their fleet to the full and can’t avoid peak flying. Most importantly, there still needs to be a mechanism to distribute the capacity available to the airlines. International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) guidance shows that peak/off-peak charges have been ineffective in prompting airlines to reschedule flights to less congested airports.

Slot auctions are a market-based measure designed to achieve efficiency in allocation. But a recent Chinese experiment at Guangzhou Baiyun and Shanghai Pudong hasn’t been repeated. The money involved would not be sustainable in the long term. And it would favor larger carriers, potentially reducing the industry to a few globally dominant carriers and destroying the low-cost carrier business model.

That would certainly limit industry growth and the many benefits it brings. It is worth noting that auctions in other sectors, such as television, mobile telephone rights and even airport concessions, have led to overbidding, forcing consumer prices up.

Even more perverse is the impact auctions could have on infrastructure development. Those receiving the auction revenue would have a huge incentive to limit capacity and maintain the huge value of the slots. Administrative allocation through slot coordination remains the best option. Following the WSG ensures transparency, certainty, consistency, and non-discrimination and is globally harmonized.

It involves an independent and neutral coordinator reviewing the equivalent season’s operations. Where airlines have been able to achieve 80% usage of each slot, they retain it through historic precedence. New requests for slots are considered against the capacity available and at least 50% of new slots are prioritized for new entrant airlines.

- airlines can enter new markets without additional entry costs;

- scarce capacity is not wasted, with airports achieving 98% utilization;

- airlines operate to markets where consumer demand exists. There is no incentive to operate empty routes, and slots are not route specific, so airlines can match slot to demand;

- there is no favoring of certain airlines, business models or the ability to pay;

- reliability and stability in schedules is balanced with the need to promote competition and access to new airlines.

Strategic review Though research and analysis has shown that the WSG is enabling consumer choice and competition, there is always room to improve. The WSG have evolved over decades and Maughan sees a need to further improve and clarify the process. With this in mind, IATA launched a strategic review of the WSG in July 2016.

- To ensure the views of all stakeholders are taken into account, the review is being undertaken in conjunction with Airports Council International (ACI) and the Worldwide Airport Coordinators Group (WWACG).

- We cannot solve the capacity crisis with the WSG, only ensure all available capacity is allocated fairly,” says Maughan.

“Making sure the WSG is as good as it can be is why we’re focusing on the strategic review.” The scope, timelines, project details, and management have been established and agreed by the three parties. Initial conclusions and recommendations will be presented to the Strategic Review Management Group by November 2018 with the review completed in 2019.

- Some early ideas might even make it into the January 2019 edition of the WSG,

- And regulators will be kept in the loop at all times.

- The review is composed of four task forces ( see The Task Forces, below ).

- Clarification on performance monitoring, a greater focus on transparency and independence, and the possibility of a revamped new entrant rule are likely to be areas of especial interest.

The timelines and process details that are involved in slot allocation will also be examined in light of today’s dynamic market and new technologies. “As the global coordinators association, with many years of experience managing the slot process at the world’s busiest airports, our members have an excellent overview of the different challenges and issues from different parts of the globe,” says Eric Herbane, COHOR (French Airport Coordination) and WWACG Chair.

“We contribute this expertise and experience in defining the best possible processes for the future WSG and therefore fully support the strategic review.” Herbane stresses that independent coordination is a key principle of the WSG, to ensure a neutral, fair and transparent approach is maintained, and while there are areas of the WSG that need review and enhancement, “broadly the policy and process work.” “The WSG is essential,” Maughan reiterates.

“If governments and airports resorted to local and unique solutions, it would cripple airlines’ efforts to provide their customers with the services their want, to the places they want to fly, when they want to fly, and at a price they want to pay. “IATA is fully committed to the WSG and its ability to support the growth of the aviation industry and certainly not reluctant to ensuring the review delivers meaningful outcomes.” The Task Forces Four task forces comprise the strategic review of the WSG:

- Slot performance monitoring. The aim is to increase the overall performance of the network by enhancing the monitoring of slots and ensuring that slots are being used correctly.

- Access. Encouraging access for new entrants is the goal, most likely through the tweaking of the new entrant rule and a better understanding of available capacity through additional requirements for transparency.

- Historic Determination. Timelines will be examined to see if they meet the demands of an increasingly dynamic industry while also accounting for an airline need for certainty so that tickets can be sold in advance.

- Level 2 airports. Guidelines for this interim level of airports need more teeth so a valid process is in place before these airports become congested.

There are 200 slot coordinated airports, with 90% following IATA’s World Slot Guidelines

How will IATA’s slot guidelines affect airport capacity?

A strategic review of IATA’s Worldwide Slot Guidelines will strengthen the allocation of ever-scarcer airport capacity  Airport capacity has become a major issue as air traffic demand continues to soar. Infrastructure isn’t being built quickly enough, creating problems for passengers and cargo. There is no substitute for the physical expansion of airports to resolve this crisis.

Airport capacity has become a major issue as air traffic demand continues to soar. Infrastructure isn’t being built quickly enough, creating problems for passengers and cargo. There is no substitute for the physical expansion of airports to resolve this crisis.

But there is a need to manage scarce capacity with a fair, neutral, and transparent system until sufficient capacity can be built. For that, IATA’s Worldwide Slot Guidelines (WSG) is critical. Despite airport capacity constraints, the WSG has enabled growth in all parts of the world. There were more than 2,000 new routes established at European slot-coordinated airports between 2010 and 2017, for example, enabling an extra 155 million passengers to travel.

‘Bloomberg Surveillance Simulcast’ Full Show 01/26/2023

Importantly, new entrants—including low-cost carriers (LCC)—have thrived under the WSG, According to Eurocontrol, LCC flights grew 61% between 2007 and 2016. The top airports for LCCs in Europe in terms of movements are Barcelona, Dusseldorf, London Gatwick, and Stansted—all level 3 airports (the most congested).

- Similar new entrant growth is seen in other regions.

- In the past five years, HKExpress has opened a dozen new routes out of Hong Kong’s essentially full airport that had no competition or only one incumbent carrier, with the effect of making all of these destinations available to far more travelers through lower fares and increased competition,” says Stephen Milstrey, Manager Network Planning and Scheduling, HKExpress.

“The historic determination guidelines in the WSG enabled this by allowing us to slowly convert generally unusable, short series of slots into valuable, full-season slots.” Full to the brim Despite the success of the WSG, there have been calls for a radical shake-up of the system and some regulators have experimented with potential alternatives.

- In large part, this has been brought on by the increasing severity of the capacity crunch.

- In a worst-case scenario, there could be more than 300 slot-coordinated airports in 10 years’ time.

- Major hubs are full to the brim and the slot pool is empty.

- Regulators are thus concerned about how to develop the process to ensure new entrants can continue to compete.

Coupled with this is a desire to improve the monitoring of slots, so that incumbents do not abuse the WSG process. In addressing these concerns, it is critical that a global system is maintained. If the system descended into individual airports pursuing their own allocation criteria, the resulting patchwork would certainly confuse and constrict the network.

Coordination is the key. A take-off slot at airport A only has value if there is a corresponding landing slot available at the other congested airport B at the right time. “As a global industry, aviation always does better with global solutions to global problems,” says Lara Maughan, IATA’s Head of Worldwide Airport Slots.

Schedule optimization The WSG maintains value even when there is nothing left in the slot pool. Slot mobility—swapping or transferring slots to other airlines in a secondary process—allows airlines to optimize schedules to meet consumer demand with speed and agility.

The majority of secondary slot exchanges take place for no monetary compensation as they allow the carriers involved in the exchanges to optimize their operation. Even at the so-called super-congested airports, airlines can eventually get access through the WSG ; Aeromexico, Air Astana, Hainan Airlines, Philippine Airlines, and Vietnam Airlines have all started operating at Heathrow in the last few years.

And once they’ve entered the market, carriers can grow, as demonstrated by HKExpress at Hong Kong International Airport. It has grown from a fleet of five aircraft to more than 20 in a short period (2013–2018). Alternatives to the WSG Many alternatives to the WSG are being proposed but each has its challenges.

Experience continues to point the industry back to the WSG. Peak/off-peak pricing means airlines wanting to operate in the most congested periods pay more for using the scarce infrastructure and so it encourages airlines to use the off-peak periods—in theory. It doesn’t work for many reasons. Market demand dictates schedules, for example, not airport pricing models.

Also, airlines must utilize their fleet to the full and can’t avoid peak flying. Most importantly, there still needs to be a mechanism to distribute the capacity available to the airlines. International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) guidance shows that peak/off-peak charges have been ineffective in prompting airlines to reschedule flights to less congested airports.

Slot auctions are a market-based measure designed to achieve efficiency in allocation. But a recent Chinese experiment at Guangzhou Baiyun and Shanghai Pudong hasn’t been repeated. The money involved would not be sustainable in the long term. And it would favor larger carriers, potentially reducing the industry to a few globally dominant carriers and destroying the low-cost carrier business model.

That would certainly limit industry growth and the many benefits it brings. It is worth noting that auctions in other sectors, such as television, mobile telephone rights and even airport concessions, have led to overbidding, forcing consumer prices up.

Even more perverse is the impact auctions could have on infrastructure development. Those receiving the auction revenue would have a huge incentive to limit capacity and maintain the huge value of the slots. Administrative allocation through slot coordination remains the best option. Following the WSG ensures transparency, certainty, consistency, and non-discrimination and is globally harmonized.

It involves an independent and neutral coordinator reviewing the equivalent season’s operations. Where airlines have been able to achieve 80% usage of each slot, they retain it through historic precedence. New requests for slots are considered against the capacity available and at least 50% of new slots are prioritized for new entrant airlines.

- airlines can enter new markets without additional entry costs;

- scarce capacity is not wasted, with airports achieving 98% utilization;

- airlines operate to markets where consumer demand exists. There is no incentive to operate empty routes, and slots are not route specific, so airlines can match slot to demand;

- there is no favoring of certain airlines, business models or the ability to pay;

- reliability and stability in schedules is balanced with the need to promote competition and access to new airlines.

Strategic review Though research and analysis has shown that the WSG is enabling consumer choice and competition, there is always room to improve. The WSG have evolved over decades and Maughan sees a need to further improve and clarify the process. With this in mind, IATA launched a strategic review of the WSG in July 2016.

To ensure the views of all stakeholders are taken into account, the review is being undertaken in conjunction with Airports Council International (ACI) and the Worldwide Airport Coordinators Group (WWACG). “We cannot solve the capacity crisis with the WSG, only ensure all available capacity is allocated fairly,” says Maughan.

“Making sure the WSG is as good as it can be is why we’re focusing on the strategic review.” The scope, timelines, project details, and management have been established and agreed by the three parties. Initial conclusions and recommendations will be presented to the Strategic Review Management Group by November 2018 with the review completed in 2019.

Some early ideas might even make it into the January 2019 edition of the WSG, And regulators will be kept in the loop at all times. The review is composed of four task forces ( see The Task Forces, below ). Clarification on performance monitoring, a greater focus on transparency and independence, and the possibility of a revamped new entrant rule are likely to be areas of especial interest.

The timelines and process details that are involved in slot allocation will also be examined in light of today’s dynamic market and new technologies. “As the global coordinators association, with many years of experience managing the slot process at the world’s busiest airports, our members have an excellent overview of the different challenges and issues from different parts of the globe,” says Eric Herbane, COHOR (French Airport Coordination) and WWACG Chair.

“We contribute this expertise and experience in defining the best possible processes for the future WSG and therefore fully support the strategic review.” Herbane stresses that independent coordination is a key principle of the WSG, to ensure a neutral, fair and transparent approach is maintained, and while there are areas of the WSG that need review and enhancement, “broadly the policy and process work.” “The WSG is essential,” Maughan reiterates.

“If governments and airports resorted to local and unique solutions, it would cripple airlines’ efforts to provide their customers with the services their want, to the places they want to fly, when they want to fly, and at a price they want to pay. “IATA is fully committed to the WSG and its ability to support the growth of the aviation industry and certainly not reluctant to ensuring the review delivers meaningful outcomes.” The Task Forces Four task forces comprise the strategic review of the WSG:

- Slot performance monitoring. The aim is to increase the overall performance of the network by enhancing the monitoring of slots and ensuring that slots are being used correctly.

- Access. Encouraging access for new entrants is the goal, most likely through the tweaking of the new entrant rule and a better understanding of available capacity through additional requirements for transparency.

- Historic Determination. Timelines will be examined to see if they meet the demands of an increasingly dynamic industry while also accounting for an airline need for certainty so that tickets can be sold in advance.

- Level 2 airports. Guidelines for this interim level of airports need more teeth so a valid process is in place before these airports become congested.

There are 200 slot coordinated airports, with 90% following IATA’s World Slot Guidelines

What are the main factors in a commercial airplane design?

I’ve resisted writing this article, as too many consultants fire off articles related to their field of expertise while using travel-related themes to make their points. This is because consultants spend so much time in airplanes and hotels, it becomes their only point of reference for many real-world activities.

James Harrington, the self-professed quality “guru,” often wrote magazine articles framed from his experiences in airports, and it was evident that his latter-day experiences were nearly entirely seen through the lens of a traveling consultant, rather than an earth-bound user of his products. It’s off-putting.

But here I am, some decades later, doing the same thing. now, however, I feel I’m more than justified since US airlines are facing a PR scandal the likes of which hasn’t been seen well, perhaps, ever. Dr. David Dao was physically dragged off a United Airlines plane by law enforcement because he wouldn’t give his seat up for double-booked airline staffers.

Another woman was reduced to tears when an American Airlines flight attendant yanked a child stroller from her, hitting her baby, and then the flight attendant nearly came to blows with another passenger, while the captain watched passively from the galley. Delta Airlines is now facing a similar backlash after rudely ejecting a family over a mis-quoted airline seating policy.

These incidents are only getting attention because passengers, armed with cell phones and Facebook accounts, can publish them; many of us traveling regularly know this stuff goes on, and never gets reported. And thank goodness for the reporting being done by passengers themselves, because the situation is worsening year by year.

In his testimony before Congress, United CEO Oscar Munoz put the blame for such incidents on a melange of half-thought-out symptoms, such as kneejerk reaction to engage law enforcement when no laws were broken, strict adherence to procedures without assessment of the real world context, and insufficient rewards offered to passengers to give up seats.

Overbooking was mentioned, but almost in passing. Munoz is no idiot, although he plays one on television apparently. He knows full well what the problems are, as do the other CEOs of Delta, American and the rest. Travelers know it too, even if they can’t put it into words.

If we apply some ISO 9001 style root cause analysis, it doesn’t take much to conclude that the root cause of all the United States’ airline woes is poor capacity management. In short, too many people in planes and in facilities that were specifically designed for a smaller number of people. Proper capacity management is a professional expertise in and of itself, utilizing the disciplines of engineering, ergonomics, human behavioral sciences, and even psychology.

It’s not easy. But airlines have unprecedented cash to invest in such work, if they choose to; the reality is that they don’t. Their one goal is to put as many people on a single plane as physically possible; operating a flight typically runs at fixed costs, for staffing, catering and fuel, with the typical fluctuations driven by current market prices and labor demands.

- But those adjustments typically move slowly, allowing airlines to plan their costs over medium- and long-range periods.

- This is especially true now, as fuel prices have stabilized.

- Nevertheless, the reality is that getting more people on a single flight, rather than operating two flights, is cheaper, and results in higher per-flight profits.

And so the airlines are obsessed with jamming in passengers, despite any previous capacity management efforts that have been made. This results in overcrowding of not only the airplanes themselves, but the ticketing counters, terminals, jetways, security lines and luggage reclaim areas.

Behavioral studies from a century or more ago already have proven that putting more people in a limited space results in stress and often outbursts of violence, so the airlines should not be surprised at the growth in passenger furor and frequent cases of airline employees “losing it” and going ballistic.

These reactions are the inevitable result of changes made by the airlines to cram in passengers. Let’s look. Luggage Airplane designers dream up a new model with capacity in mind. Yes, they love to announce a new plane is going to feature a “bowling alley, a movie theater and a nightclub” but no one believes that; I’ve seen the same promises in old issues of Popular Science, and never once have seen a Delta or American Airlines plane with a bowling alley.

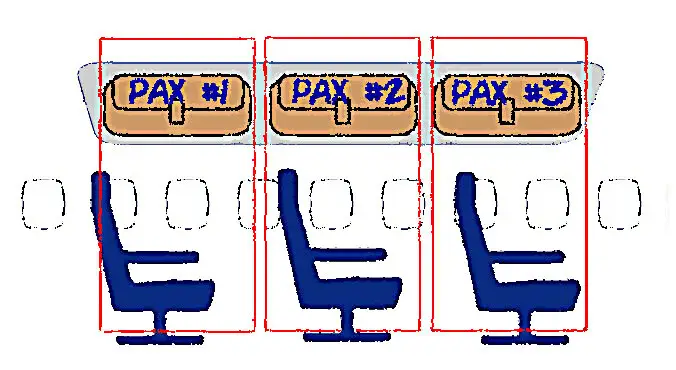

- Instead, one of the main factors in any commercial airplane design effort is always passenger capacity, along with cargo capacity, fuel capacity, and then the expected mechanical considerations, like structure, engines, aerodynamics, etc.

- But the process is keenly linked to an estimated total passenger capacity, since ultimately commercial planes are tasked with moving asses through the air.

The airplane manufacturers have a standard volume space they assume a single passenger occupies, and then they work up from there. They then build the aircraft with the passenger cabins considered “empty,” because the airline customers will then make their own demands on how the passenger “loadout” will be configured.

- One airline may purchase a number of jetliners with each holding 150 passengers, assorted into different classes (first, business, economy, etc.) Another airline may purchase the same airplane, but request that it hold 250 passengers in only one class (economy).

- Another may yet request it be configured for 300 or more passengers.

The airplane manufacturers will then build the interiors accordingly, use subcontract firms to do so, or the airline itself may have subcontractors do it; or it can be any combination of these. Eventually, the planes are delivered as configured by the purchasing airline.

Even then, once an airplane is purchased and operated, it can be reconfigured years later to add seats beyond what it was originally configured for. The problem is that an airplane’s outer structure is fixed, so its inner capacity is fixed, too. A plane designed to hold 300 passengers cannot suddenly hold 1,000, no matter how much the buying airline wants it to, unless they strip out things like the engines, landing gear assembly, electrical systems and the cockpit; it’s an idea Spirit Airlines is probably considering, too.

Luggage is also relatively fixed in size, and the size of human beings is known and fixed, even giving consideration to different heights and weights; airplanes don’t have to accommodate 9-foot tall, 600 lb, three-headed giants, for example. Westeros Airlines maybe, but not Delta.

But when airlines compress seating to fit in more passengers, this breaks some basic considerations, and even laws of physics. If an airplane is designed to seat three people in a given space, the luggage space above is thus configured to handle three pieces of luggage of the airline’s pre-established and approved sizes.

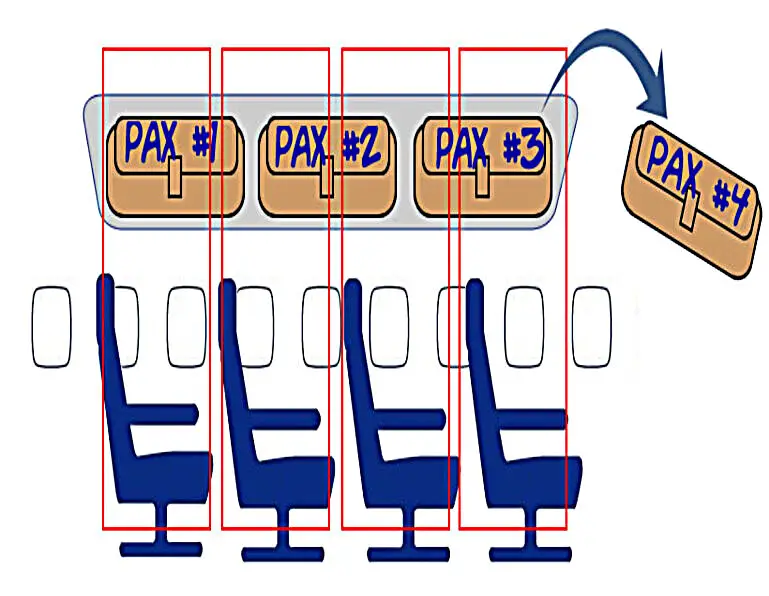

That might look like this:  When the airline re-configures the space to insert a fourth passenger seat in the same space, it does a number of things that defy physics and increase stress and irritation. First, it reduces legroom, which causes passengers physical discomfort. This simultaneously reduces space for smaller, under-seat carry-on bags as well.

When the airline re-configures the space to insert a fourth passenger seat in the same space, it does a number of things that defy physics and increase stress and irritation. First, it reduces legroom, which causes passengers physical discomfort. This simultaneously reduces space for smaller, under-seat carry-on bags as well.  Airlines don’t care what’s in that piece of luggage you may have carefully packed with the assumption you’d be able to bring it on board. Seasoned travelers know not to put sensitive electronics or valuables into checked bags, because the airlines have such poor security and handling procedures, there’s a good chance items will be damaged or stolen.

Airlines don’t care what’s in that piece of luggage you may have carefully packed with the assumption you’d be able to bring it on board. Seasoned travelers know not to put sensitive electronics or valuables into checked bags, because the airlines have such poor security and handling procedures, there’s a good chance items will be damaged or stolen.

- So most people will pack their valuables in the carry-on bags, only to be confronted by irritated flight attendants demanding they suddenly check their bags anyway, because the luggage space is full.

- Arguments ensue, and for valid reasons: the airline is not about to reimburse a passenger if their camera equipment or computer is broken when tossed around by the baggage handlers, nor are they going to admit their staff stole jewelry out of it.

The staffers fight back because they operate to procedures, and can’t process the experience of customers. It gets more ludicrous when the flight attendant announces that you’ll have to check your bags only after you remove your “lithium batteries, valuables, or any fragile items,” because they’ve just invited you to violate their other policy, which says you can’t sit with a lap-full of loose items which can become projectiles in the event of turbulence.

- They also balk if you stuff the seat pocket with these items, resulting in more self-inflicted chaos and arguments between passengers and flight staff.

- Their own procedures don’t even agree with each other.

- The airlines operate in a dreamy world where they think if they add more seats, passengers will just know this psychically, so while they are still at home packing, they will consider this and simply bring less luggage.

And mind you, this means less luggage then their own airline policies say you can bring. They want everyone walking on planes with a wallet or handbag, some cologne and a happy smile. That’s it. It defies human behavior. Lines Lines Lines Next, an increase in passengers means more people are placed into spaces within the airport that were not designed for large crowds.

- An airport is built at a point in time, with a planned capacity being a key component in its architectural design and physical layout.

- Its capacity is relatively fixed, and cannot be increased or reconfigured at the same rate of speed that an airline can add additional seats to a fleet of airplanes.

- Structural additions or changes to airport facilities require long-term engineering studies, planning, and often statutory and regulatory approval at multiple levels of government.

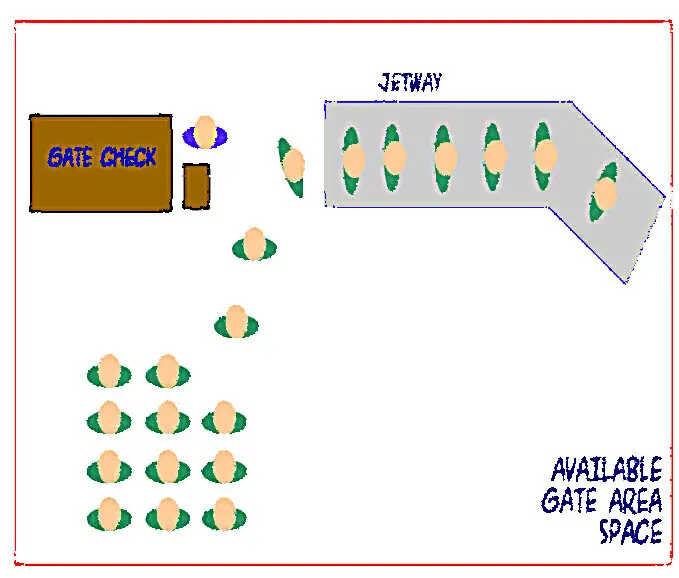

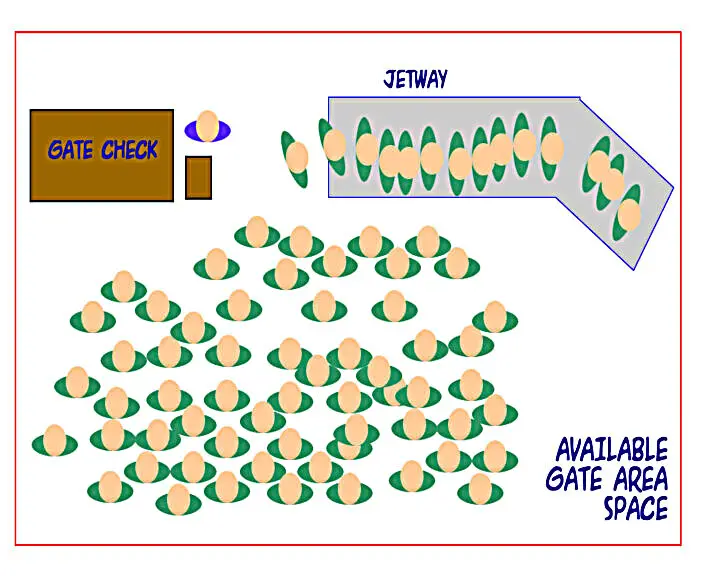

Not to mention millions, if not billions, of dollars in investments. So whereas an airport may be built in 1980 to allow for a set number of people, based on 1980’s typical airline capacity, a typical gate may look like this:  That airport cannot quickly add square footage to accommodate changes made to each airline’s increased passenger capacity, so in a few years that same gate looks like this:

That airport cannot quickly add square footage to accommodate changes made to each airline’s increased passenger capacity, so in a few years that same gate looks like this:  The physical space allotted for the gate has not changed. The square footage is the same, the number of ticket scanning podiums (typically 1 or 2) is the same, the width of the jetway is the same. The single loading door of the front of the airplane has not changed.

The physical space allotted for the gate has not changed. The square footage is the same, the number of ticket scanning podiums (typically 1 or 2) is the same, the width of the jetway is the same. The single loading door of the front of the airplane has not changed.

The only thing that has increased is the crowd, Simple laws of science tell us now that passenger loading will take longer, since more passengers have to pass through a fixed space that was designed for fewer people, and thus the physical space between passengers will decrease. This increases hostility, irritation, stress, and the likelihood of an altercation.

It even increases the risk of physical injury, as people with backpacks accidentally smack into those behind them, or wheelchairs run over standing passengers, or children are stepped on. The increase of stress and risk is true for passengers as well as airline staff.

- The constant yelling by gate attendants, insisting that loading time is a function of the passengers’ ability to listen to directions and “take your seats quickly,” isn’t helping.

- We all know that’s nonsense, and anyone simply looking at a massive, congested crowd knows the problem is the number of people, not how fast they can “step into your aisle and allow others to pass.” Planes aren’t delayed because of people sitting too slowly, they’re delayed because airlines are greedy.

United States of Shouting Then there are the odd policies adopted by the US airlines, airports and security agencies. Those of us who travel internationally often know that arriving at a US airport, after a long time out of the country, points out the problems with our national policies immediately.

You are greeted, suddenly, by hostile employees of the airlines, airports and TSA, and treated as stupid. Then the shouting begins; my God, the shouting, At no other country’s airport are you shouted at by so many employees, each one treating you as an ignorant savage, talking down with condescension while barely able to contain their own loathing for their jobs.

They’d rather not be there, and as their way of self-expression, they are going to take it out on you. And the policies of those organizations involved hand them the procedural tools to do just that. I’ve traveled to Europe, Asia and all through the Americas, so I do admit to not being up to speed on travel in the Middle East, Russia or Africa.

But my experiences, even with low-cost budget third world airlines, still proves that the US air experience is one of the worst in the world. This is due to not only poor training, but poorly designed training. The procedures and training given to American airline and airport staff not only does not aim to reduce conflict, it actually ensures it.

It’s likely the training is designed by equally irritated airline staff who likewise really don’t give a shit about passengers. Take, for example, the simple failure to raise your tray table prior to landing, whether because you forgot or were being petulant.

In other countries, the staff are trained to simply reach in, and raise the tray for you. They don’t speak; this is because other nations don’t assume their language is the only language in the world, and they know that you may simply not be able to understand them. They reach in, raise the tray, and there is no conflict.

Ditto for the seat back; they reach in, press the button with one hand, and raise your seat with the other. In silence. They move on, and the problem is corrected. In the US, however, the flight attendants are trained to bark orders, in English, and demand that you raise your tray table yourself.

- The interaction is immediately hostile: you are doing something wrong, and you are verbally berated in front of everyone else on the plane.

- If you don’t comply, they won’t raise the tray table themselves, but instead launch into an extended lecture, condescending and irritable, blaming you for putting the airplane’s landing at risk.

It’s ludicrous, of course, because ultimately it’s the flight attendant that is dragging out the process and causing risk to the landing procedures, rather than simply raising the tray table; but US flight attendants are trained to harass and berate passengers, all for the purposes of quoting procedures and humiliating someone they see as a nonconforming customer.

- And heaven help you if you don’t understand the English they’re shouting at you in, because then you’re not only violating airline policy, you’re an ignorant savage to boot, you dirty underworlder.

- The US Transportation Security Agency (TSA) has won worldwide fame as being one of the most incompetent, poorly trained fleet of badged personnel on the planet, and it’s well-earned reputation.

Their training is so abysmal, their behavior defies belief when you begin to notice it. First, unlike any other country, you are confronted with shouting. And a lot of it. Whereas other countries put up signs, often in multiple languages, the US’ arrogant “we speak English, bitches” assumptions means that you won’t have signs in many airports, and so the TSA agents have to scream instructions at you.

And of course, they do this in English. You know the script. ” People,” — they always start with the word “people,” which sets the condescending tone immediately — ” people, you have to remove your liquids, put your laptops in a tray by themselves, and place your shoes directly on the belt! ” You’ve heard that, shouted over and over, until the TSA agents appear literally blue in the face.

Worse, they don’t hire TSA agents on their public speaking abilities, and assign these “shouting” duties to anyone, including the tiny, mousy-voiced employees who couldn’t be heard over the noise of the PA announcements if they blurted out a gut-inverting primal scream.

But if you don’t hear them, if you don’t speak English — and only to TSA is it a shock that international travelers may not speak English –, or if you don’t understand them for any reason, the fault is yours and yours alone. Then you’ll be faced with the second speech, also shouted at you: “People, the reason these lines are so long is because you’re not removing your liquids! This will all go faster if you just pay attention and do as I tell you!” It’s nonsense of course, but the TSA agents are trained to believe it.

They don’t know the airport security area was originally built to process only 2,000 passengers per hour, and when the crowd is 5,000 strong the system essentially breaks down. They don’t care, either, since they are typically low-paid and given a badge, which is always a recipe for disaster.

- Many TSA agents are not regular fliers, so they never experience their work as a customer of it, alienating them further from the hassles they impose on people.

- The same physical constraints apply to the screening area as to the gate area: the physical area was designed to accommodate a set number of people, and thanks to airline capacity increases, those areas find more people being shoved through to get on the same number of airplanes.

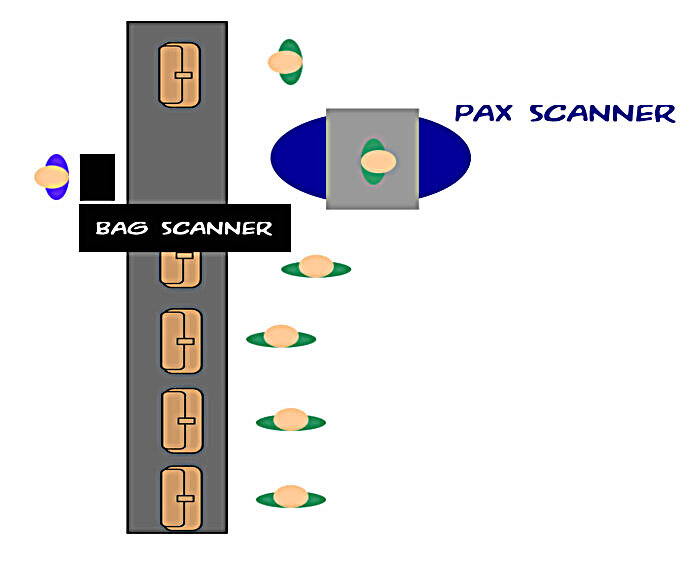

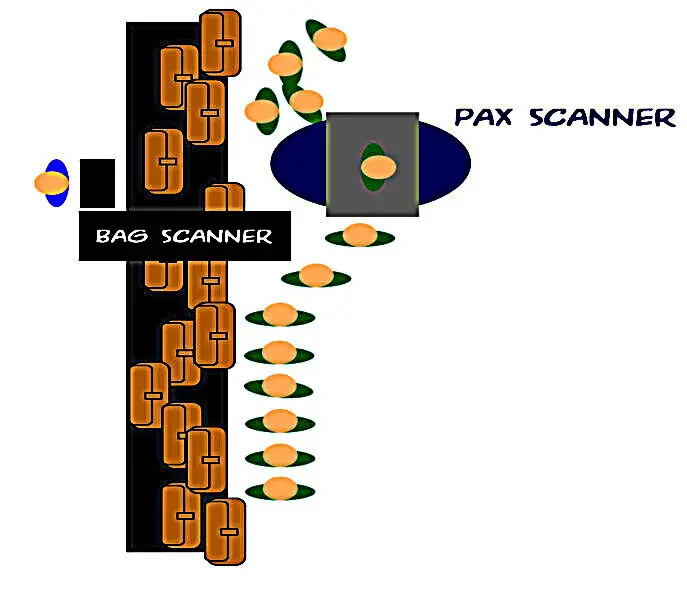

So whereas a security screening area might have been designed like this:  thanks to airline capacity glut, the eventual area looks like this, increasing confusion, pushing equipment to its limits, increasing security line delays, forcing TSA staffing issues, and overall dramatically increasing stress on both passengers and TSA agents:

thanks to airline capacity glut, the eventual area looks like this, increasing confusion, pushing equipment to its limits, increasing security line delays, forcing TSA staffing issues, and overall dramatically increasing stress on both passengers and TSA agents:  Worse still, this overcrowding results in a reduction in TSA’s primary function: airport security. The chaos at the security screening area is the weakest link — not the strongest — when it comes to enabling people to switch bags, steal property, and cause altercations.

Worse still, this overcrowding results in a reduction in TSA’s primary function: airport security. The chaos at the security screening area is the weakest link — not the strongest — when it comes to enabling people to switch bags, steal property, and cause altercations.

It’s been well documented that the screenings don’t work, either, and that while the best equipment in the world can be given to TSA to screen passengers and bags, the training of TSA agents is so poor, and the work so mind-numbing, that nearly all dummy explosive devices were able to pass through screening during recent testing,

Factor in the crowds, heightened stress over the risks of having your luggage stolen as you are separated from it, and incessant shouting by TSA agents ( “People! People, listen up!! “) and it’s a recipe for conflict and agitation. Mexico City paints a picture of what US airports are becoming, quickly.

- Aeromexico, which routs the majority of its flights through its hub at Aeropuerto Internacional Benito Juárez; the airport is physically small, and simply cannot handle the capacity.

- Making matter worse, Mexican regulations require all passengers to go through customs and security even if they are merely passing through on a layover, because the facility does not have a separate area to process passengers flying internationally.

This means everyone must stand on a line for immigration, and fill out immigration paperwork, even for a 30-minute layover; and then everyone must gather their luggage and undergo multiple screenings, including (often) a hand-screening, of luggage. The average wait for this process is 2 hours, but can take up to 4, since the physical layout of the building only allows four immigration officers to process the thousands of people passing through ever hour.

- We see airports such as Denver and Houston already turning into this, slowly, but piling on the additional US problems of English-only shouting and overall treatment of passengers as criminals, making the experience even worse than Mexico.

- In Peru I am able to board a plane that has every single carry-on bag hand-screened before I get on the jetway, and the experience is still more polite, faster and less stressful than a simple domestic “hopper” flight from Orlando to Miami.

So while the CEOs of various airlines face the US Congress and the growing anger of passengers, they will feign ignorance, or — like Munoz — post smug and tone deaf excuses. They will insist that if things are so bad, then people wouldn’t fly, ignoring the growing realities that necessitate the increase in air travel.

How does increased capacity affect airlines’ on-time performance?

Margins Are Tightening For US Airlines As Capacity Growth Keeps Outpacing GDP US airlines ejoyed eight straight years of profitability. But it’s getting harder. Getty Dirk Lehmhus EyeEM While airlines in the United States stretched their unbroken string of operating profits to eight years in 2018, they’re facing tough choices moving forward as costs rise and margins narrow.

- Persistently strong demand for air travel is pushing many carriers to add capacity, but the additional routes and service are making pricing more competitive and putting pressure on yields.

- Based on current trends and pressures, the operating margin for US airlines is expected to narrow to between five and six percent in 2019 — a margin that is less than 40 percent of the industry’s peak of 15 percent in 2015.

Given the potential for a global economic slowdown in 2019 and 2020, reversing the decline in profit margins will become more of a challenge. Margins were squeezed in 2018 as well. They fell to 9.2 percent from 12.7 percent the previous year, marking the third straight year that US airline margins have contracted.

The calculations and analysis are based on research on 10 prominent US airlines for the, New pressures The increased capacity is also making it increasingly difficult for airlines to keep up their operational resilience and stick to published schedules. On-time performance in North America dropped to 74.5 percent in February 2019 from 78.7 percent in February 2018 and 81.5 percent in 2017.

Additionally, the impact of capacity growth on an already severely constrained infrastructure and overly congested airspace and airports must be addressed. Based on the global struggle to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, the airline industry will likely contend with mounting pressure from governments and the public to do its part, even as available seat miles and the number of flights increase.

The global fleet alone is, Airlines will have to figure out a way to cut fuel usage as they grow capacity, or face rising carbon offset payments under, Capacity growth There’s no doubt that the rising demand for air travel is encouraging airlines to focus on the need for new capacity and the potential to expand revenue and market share — even if such moves mean potentially sacrificing margins and reducing yield.

This year’s Airline Economic Analysis reinforces earlier findings that adding capacity at a pace faster than US economic growth has contributed to carriers’ eroding margins over the past several years. This is a situation likely to continue until a balance between supply and demand is restored.

- Even as oil and jet fuel prices decline, airline margins drop.

- Oliver Wyman In 2014, capacity began to expand faster than the US gross domestic product (GDP) — much faster, in fact.

- That year, GDP grew 2.5 percent versus capacity growth well above three percent.

- By 2015, capacity growth was peaking above four percent, while GDP was 2.9 percent.

Industry margins reached 15 percent, helped by oil prices that averaged around $50 a barrel. GDP took a sudden slide in 2016 to below two percent as the trade deficit ballooned and oil prices plunged. While airline capacity growth also began to slow, it failed to match the drop in GDP.

That’s when margins began to fall, despite lower oil prices. Even with cheaper oil In January 2016, prices per barrel slid to around $35 from a high of more than $110 in 2014. Although prices quickly recovered to above $50, they have not returned to the $80-plus levels they had maintained between mid-2009 and October 2014.

While fuel typically makes up between 25 and 30 percent of total operating costs for carriers and represents the industry’s second-largest expense, the pattern of margin decline makes it clear that many factors other than fuel — most notably labor, the No.1 expense, and capacity — affect profitability as much or more over the medium to long term.

- One caveat: While margins have tightened since 2015, they are still higher than they were from 2010 to 2013, when they were six percent or lower and oil prices were consistently above $80.

- The fact that margins were in the teens from 2015 to 2017, even though on the decline, reflects the impact of lower oil prices.

While airlines remain profitable, the prospect of slowing GDP may force carriers to reassess capacity expansions, especially given rising pressures on operations from that rapid growth. Indeed, the industry’s biggest risk over the next decade may be failing to strike the right balance between capacity and profitability at a time when managing operations grows increasingly difficult.

- Oliver Wyman’s Grant Alport, Andy Buchanan, and Aaron Taylor contributed to the research and insights in the 2019 Airline Economic Analysis and in this article.

- Grant is a principal, based in Washington DC, in the transportation practice.

- Andy is a vice president, based in Chicago, in the transportation practice.

Aaron is a senior manager in the transportation practice who handles Oliver Wyman’s aviation business intelligence offering, : Margins Are Tightening For US Airlines As Capacity Growth Keeps Outpacing GDP

Is airport capacity a problem?

A strategic review of IATA’s Worldwide Slot Guidelines will strengthen the allocation of ever-scarcer airport capacity  Airport capacity has become a major issue as air traffic demand continues to soar. Infrastructure isn’t being built quickly enough, creating problems for passengers and cargo. There is no substitute for the physical expansion of airports to resolve this crisis.

Airport capacity has become a major issue as air traffic demand continues to soar. Infrastructure isn’t being built quickly enough, creating problems for passengers and cargo. There is no substitute for the physical expansion of airports to resolve this crisis.

- But there is a need to manage scarce capacity with a fair, neutral, and transparent system until sufficient capacity can be built.

- For that, IATA’s Worldwide Slot Guidelines (WSG) is critical.

- Despite airport capacity constraints, the WSG has enabled growth in all parts of the world.

- There were more than 2,000 new routes established at European slot-coordinated airports between 2010 and 2017, for example, enabling an extra 155 million passengers to travel.

Importantly, new entrants—including low-cost carriers (LCC)—have thrived under the WSG, According to Eurocontrol, LCC flights grew 61% between 2007 and 2016. The top airports for LCCs in Europe in terms of movements are Barcelona, Dusseldorf, London Gatwick, and Stansted—all level 3 airports (the most congested).

- Similar new entrant growth is seen in other regions.

- In the past five years, HKExpress has opened a dozen new routes out of Hong Kong’s essentially full airport that had no competition or only one incumbent carrier, with the effect of making all of these destinations available to far more travelers through lower fares and increased competition,” says Stephen Milstrey, Manager Network Planning and Scheduling, HKExpress.

“The historic determination guidelines in the WSG enabled this by allowing us to slowly convert generally unusable, short series of slots into valuable, full-season slots.” Full to the brim Despite the success of the WSG, there have been calls for a radical shake-up of the system and some regulators have experimented with potential alternatives.

- In large part, this has been brought on by the increasing severity of the capacity crunch.

- In a worst-case scenario, there could be more than 300 slot-coordinated airports in 10 years’ time.

- Major hubs are full to the brim and the slot pool is empty.

- Regulators are thus concerned about how to develop the process to ensure new entrants can continue to compete.

Coupled with this is a desire to improve the monitoring of slots, so that incumbents do not abuse the WSG process. In addressing these concerns, it is critical that a global system is maintained. If the system descended into individual airports pursuing their own allocation criteria, the resulting patchwork would certainly confuse and constrict the network.

Coordination is the key. A take-off slot at airport A only has value if there is a corresponding landing slot available at the other congested airport B at the right time. “As a global industry, aviation always does better with global solutions to global problems,” says Lara Maughan, IATA’s Head of Worldwide Airport Slots.

Schedule optimization The WSG maintains value even when there is nothing left in the slot pool. Slot mobility—swapping or transferring slots to other airlines in a secondary process—allows airlines to optimize schedules to meet consumer demand with speed and agility.

- The majority of secondary slot exchanges take place for no monetary compensation as they allow the carriers involved in the exchanges to optimize their operation.

- Even at the so-called super-congested airports, airlines can eventually get access through the WSG ; Aeromexico, Air Astana, Hainan Airlines, Philippine Airlines, and Vietnam Airlines have all started operating at Heathrow in the last few years.

And once they’ve entered the market, carriers can grow, as demonstrated by HKExpress at Hong Kong International Airport. It has grown from a fleet of five aircraft to more than 20 in a short period (2013–2018). Alternatives to the WSG Many alternatives to the WSG are being proposed but each has its challenges.

- Experience continues to point the industry back to the WSG.

- Peak/off-peak pricing means airlines wanting to operate in the most congested periods pay more for using the scarce infrastructure and so it encourages airlines to use the off-peak periods—in theory.

- It doesn’t work for many reasons.

- Market demand dictates schedules, for example, not airport pricing models.

Also, airlines must utilize their fleet to the full and can’t avoid peak flying. Most importantly, there still needs to be a mechanism to distribute the capacity available to the airlines. International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) guidance shows that peak/off-peak charges have been ineffective in prompting airlines to reschedule flights to less congested airports.

- Slot auctions are a market-based measure designed to achieve efficiency in allocation.

- But a recent Chinese experiment at Guangzhou Baiyun and Shanghai Pudong hasn’t been repeated.

- The money involved would not be sustainable in the long term.

- And it would favor larger carriers, potentially reducing the industry to a few globally dominant carriers and destroying the low-cost carrier business model.

That would certainly limit industry growth and the many benefits it brings. It is worth noting that auctions in other sectors, such as television, mobile telephone rights and even airport concessions, have led to overbidding, forcing consumer prices up.

- Even more perverse is the impact auctions could have on infrastructure development.

- Those receiving the auction revenue would have a huge incentive to limit capacity and maintain the huge value of the slots.

- Administrative allocation through slot coordination remains the best option.

- Following the WSG ensures transparency, certainty, consistency, and non-discrimination and is globally harmonized.

It involves an independent and neutral coordinator reviewing the equivalent season’s operations. Where airlines have been able to achieve 80% usage of each slot, they retain it through historic precedence. New requests for slots are considered against the capacity available and at least 50% of new slots are prioritized for new entrant airlines.

- airlines can enter new markets without additional entry costs;

- scarce capacity is not wasted, with airports achieving 98% utilization;

- airlines operate to markets where consumer demand exists. There is no incentive to operate empty routes, and slots are not route specific, so airlines can match slot to demand;

- there is no favoring of certain airlines, business models or the ability to pay;

- reliability and stability in schedules is balanced with the need to promote competition and access to new airlines.

Strategic review Though research and analysis has shown that the WSG is enabling consumer choice and competition, there is always room to improve. The WSG have evolved over decades and Maughan sees a need to further improve and clarify the process. With this in mind, IATA launched a strategic review of the WSG in July 2016.

- To ensure the views of all stakeholders are taken into account, the review is being undertaken in conjunction with Airports Council International (ACI) and the Worldwide Airport Coordinators Group (WWACG).

- We cannot solve the capacity crisis with the WSG, only ensure all available capacity is allocated fairly,” says Maughan.

“Making sure the WSG is as good as it can be is why we’re focusing on the strategic review.” The scope, timelines, project details, and management have been established and agreed by the three parties. Initial conclusions and recommendations will be presented to the Strategic Review Management Group by November 2018 with the review completed in 2019.

- Some early ideas might even make it into the January 2019 edition of the WSG,

- And regulators will be kept in the loop at all times.

- The review is composed of four task forces ( see The Task Forces, below ).

- Clarification on performance monitoring, a greater focus on transparency and independence, and the possibility of a revamped new entrant rule are likely to be areas of especial interest.

The timelines and process details that are involved in slot allocation will also be examined in light of today’s dynamic market and new technologies. “As the global coordinators association, with many years of experience managing the slot process at the world’s busiest airports, our members have an excellent overview of the different challenges and issues from different parts of the globe,” says Eric Herbane, COHOR (French Airport Coordination) and WWACG Chair.

We contribute this expertise and experience in defining the best possible processes for the future WSG and therefore fully support the strategic review.” Herbane stresses that independent coordination is a key principle of the WSG, to ensure a neutral, fair and transparent approach is maintained, and while there are areas of the WSG that need review and enhancement, “broadly the policy and process work.” “The WSG is essential,” Maughan reiterates.

“If governments and airports resorted to local and unique solutions, it would cripple airlines’ efforts to provide their customers with the services their want, to the places they want to fly, when they want to fly, and at a price they want to pay. “IATA is fully committed to the WSG and its ability to support the growth of the aviation industry and certainly not reluctant to ensuring the review delivers meaningful outcomes.” The Task Forces Four task forces comprise the strategic review of the WSG:

- Slot performance monitoring. The aim is to increase the overall performance of the network by enhancing the monitoring of slots and ensuring that slots are being used correctly.

- Access. Encouraging access for new entrants is the goal, most likely through the tweaking of the new entrant rule and a better understanding of available capacity through additional requirements for transparency.

- Historic Determination. Timelines will be examined to see if they meet the demands of an increasingly dynamic industry while also accounting for an airline need for certainty so that tickets can be sold in advance.

- Level 2 airports. Guidelines for this interim level of airports need more teeth so a valid process is in place before these airports become congested.

There are 200 slot coordinated airports, with 90% following IATA’s World Slot Guidelines

How will IATA’s slot guidelines affect airport capacity?

A strategic review of IATA’s Worldwide Slot Guidelines will strengthen the allocation of ever-scarcer airport capacity  Airport capacity has become a major issue as air traffic demand continues to soar. Infrastructure isn’t being built quickly enough, creating problems for passengers and cargo. There is no substitute for the physical expansion of airports to resolve this crisis.

Airport capacity has become a major issue as air traffic demand continues to soar. Infrastructure isn’t being built quickly enough, creating problems for passengers and cargo. There is no substitute for the physical expansion of airports to resolve this crisis.

But there is a need to manage scarce capacity with a fair, neutral, and transparent system until sufficient capacity can be built. For that, IATA’s Worldwide Slot Guidelines (WSG) is critical. Despite airport capacity constraints, the WSG has enabled growth in all parts of the world. There were more than 2,000 new routes established at European slot-coordinated airports between 2010 and 2017, for example, enabling an extra 155 million passengers to travel.

Importantly, new entrants—including low-cost carriers (LCC)—have thrived under the WSG, According to Eurocontrol, LCC flights grew 61% between 2007 and 2016. The top airports for LCCs in Europe in terms of movements are Barcelona, Dusseldorf, London Gatwick, and Stansted—all level 3 airports (the most congested).

Similar new entrant growth is seen in other regions. “In the past five years, HKExpress has opened a dozen new routes out of Hong Kong’s essentially full airport that had no competition or only one incumbent carrier, with the effect of making all of these destinations available to far more travelers through lower fares and increased competition,” says Stephen Milstrey, Manager Network Planning and Scheduling, HKExpress.

“The historic determination guidelines in the WSG enabled this by allowing us to slowly convert generally unusable, short series of slots into valuable, full-season slots.” Full to the brim Despite the success of the WSG, there have been calls for a radical shake-up of the system and some regulators have experimented with potential alternatives.

In large part, this has been brought on by the increasing severity of the capacity crunch. In a worst-case scenario, there could be more than 300 slot-coordinated airports in 10 years’ time. Major hubs are full to the brim and the slot pool is empty. Regulators are thus concerned about how to develop the process to ensure new entrants can continue to compete.

Coupled with this is a desire to improve the monitoring of slots, so that incumbents do not abuse the WSG process. In addressing these concerns, it is critical that a global system is maintained. If the system descended into individual airports pursuing their own allocation criteria, the resulting patchwork would certainly confuse and constrict the network.

- Coordination is the key.

- A take-off slot at airport A only has value if there is a corresponding landing slot available at the other congested airport B at the right time.

- As a global industry, aviation always does better with global solutions to global problems,” says Lara Maughan, IATA’s Head of Worldwide Airport Slots.

Schedule optimization The WSG maintains value even when there is nothing left in the slot pool. Slot mobility—swapping or transferring slots to other airlines in a secondary process—allows airlines to optimize schedules to meet consumer demand with speed and agility.

- The majority of secondary slot exchanges take place for no monetary compensation as they allow the carriers involved in the exchanges to optimize their operation.

- Even at the so-called super-congested airports, airlines can eventually get access through the WSG ; Aeromexico, Air Astana, Hainan Airlines, Philippine Airlines, and Vietnam Airlines have all started operating at Heathrow in the last few years.

And once they’ve entered the market, carriers can grow, as demonstrated by HKExpress at Hong Kong International Airport. It has grown from a fleet of five aircraft to more than 20 in a short period (2013–2018). Alternatives to the WSG Many alternatives to the WSG are being proposed but each has its challenges.

- Experience continues to point the industry back to the WSG.

- Peak/off-peak pricing means airlines wanting to operate in the most congested periods pay more for using the scarce infrastructure and so it encourages airlines to use the off-peak periods—in theory.

- It doesn’t work for many reasons.

- Market demand dictates schedules, for example, not airport pricing models.

Also, airlines must utilize their fleet to the full and can’t avoid peak flying. Most importantly, there still needs to be a mechanism to distribute the capacity available to the airlines. International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) guidance shows that peak/off-peak charges have been ineffective in prompting airlines to reschedule flights to less congested airports.

Slot auctions are a market-based measure designed to achieve efficiency in allocation. But a recent Chinese experiment at Guangzhou Baiyun and Shanghai Pudong hasn’t been repeated. The money involved would not be sustainable in the long term. And it would favor larger carriers, potentially reducing the industry to a few globally dominant carriers and destroying the low-cost carrier business model.

That would certainly limit industry growth and the many benefits it brings. It is worth noting that auctions in other sectors, such as television, mobile telephone rights and even airport concessions, have led to overbidding, forcing consumer prices up.

Even more perverse is the impact auctions could have on infrastructure development. Those receiving the auction revenue would have a huge incentive to limit capacity and maintain the huge value of the slots. Administrative allocation through slot coordination remains the best option. Following the WSG ensures transparency, certainty, consistency, and non-discrimination and is globally harmonized.

It involves an independent and neutral coordinator reviewing the equivalent season’s operations. Where airlines have been able to achieve 80% usage of each slot, they retain it through historic precedence. New requests for slots are considered against the capacity available and at least 50% of new slots are prioritized for new entrant airlines.

- airlines can enter new markets without additional entry costs;

- scarce capacity is not wasted, with airports achieving 98% utilization;

- airlines operate to markets where consumer demand exists. There is no incentive to operate empty routes, and slots are not route specific, so airlines can match slot to demand;

- there is no favoring of certain airlines, business models or the ability to pay;

- reliability and stability in schedules is balanced with the need to promote competition and access to new airlines.

Strategic review Though research and analysis has shown that the WSG is enabling consumer choice and competition, there is always room to improve. The WSG have evolved over decades and Maughan sees a need to further improve and clarify the process. With this in mind, IATA launched a strategic review of the WSG in July 2016.

To ensure the views of all stakeholders are taken into account, the review is being undertaken in conjunction with Airports Council International (ACI) and the Worldwide Airport Coordinators Group (WWACG). “We cannot solve the capacity crisis with the WSG, only ensure all available capacity is allocated fairly,” says Maughan.

“Making sure the WSG is as good as it can be is why we’re focusing on the strategic review.” The scope, timelines, project details, and management have been established and agreed by the three parties. Initial conclusions and recommendations will be presented to the Strategic Review Management Group by November 2018 with the review completed in 2019.

Some early ideas might even make it into the January 2019 edition of the WSG, And regulators will be kept in the loop at all times. The review is composed of four task forces ( see The Task Forces, below ). Clarification on performance monitoring, a greater focus on transparency and independence, and the possibility of a revamped new entrant rule are likely to be areas of especial interest.

The timelines and process details that are involved in slot allocation will also be examined in light of today’s dynamic market and new technologies. “As the global coordinators association, with many years of experience managing the slot process at the world’s busiest airports, our members have an excellent overview of the different challenges and issues from different parts of the globe,” says Eric Herbane, COHOR (French Airport Coordination) and WWACG Chair.

“We contribute this expertise and experience in defining the best possible processes for the future WSG and therefore fully support the strategic review.” Herbane stresses that independent coordination is a key principle of the WSG, to ensure a neutral, fair and transparent approach is maintained, and while there are areas of the WSG that need review and enhancement, “broadly the policy and process work.” “The WSG is essential,” Maughan reiterates.

“If governments and airports resorted to local and unique solutions, it would cripple airlines’ efforts to provide their customers with the services their want, to the places they want to fly, when they want to fly, and at a price they want to pay. “IATA is fully committed to the WSG and its ability to support the growth of the aviation industry and certainly not reluctant to ensuring the review delivers meaningful outcomes.” The Task Forces Four task forces comprise the strategic review of the WSG:

- Slot performance monitoring. The aim is to increase the overall performance of the network by enhancing the monitoring of slots and ensuring that slots are being used correctly.

- Access. Encouraging access for new entrants is the goal, most likely through the tweaking of the new entrant rule and a better understanding of available capacity through additional requirements for transparency.

- Historic Determination. Timelines will be examined to see if they meet the demands of an increasingly dynamic industry while also accounting for an airline need for certainty so that tickets can be sold in advance.

- Level 2 airports. Guidelines for this interim level of airports need more teeth so a valid process is in place before these airports become congested.

There are 200 slot coordinated airports, with 90% following IATA’s World Slot Guidelines

Is rising demand for air travel affecting airline margins and yields?

Margins Are Tightening For US Airlines As Capacity Growth Keeps Outpacing GDP US airlines ejoyed eight straight years of profitability. But it’s getting harder. Getty Dirk Lehmhus EyeEM While airlines in the United States stretched their unbroken string of operating profits to eight years in 2018, they’re facing tough choices moving forward as costs rise and margins narrow.

Persistently strong demand for air travel is pushing many carriers to add capacity, but the additional routes and service are making pricing more competitive and putting pressure on yields. Based on current trends and pressures, the operating margin for US airlines is expected to narrow to between five and six percent in 2019 — a margin that is less than 40 percent of the industry’s peak of 15 percent in 2015.

Given the potential for a global economic slowdown in 2019 and 2020, reversing the decline in profit margins will become more of a challenge. Margins were squeezed in 2018 as well. They fell to 9.2 percent from 12.7 percent the previous year, marking the third straight year that US airline margins have contracted.

- The calculations and analysis are based on research on 10 prominent US airlines for the,

- New pressures The increased capacity is also making it increasingly difficult for airlines to keep up their operational resilience and stick to published schedules.

- On-time performance in North America dropped to 74.5 percent in February 2019 from 78.7 percent in February 2018 and 81.5 percent in 2017.

Additionally, the impact of capacity growth on an already severely constrained infrastructure and overly congested airspace and airports must be addressed. Based on the global struggle to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, the airline industry will likely contend with mounting pressure from governments and the public to do its part, even as available seat miles and the number of flights increase.

- The global fleet alone is,

- Airlines will have to figure out a way to cut fuel usage as they grow capacity, or face rising carbon offset payments under,

- Capacity growth There’s no doubt that the rising demand for air travel is encouraging airlines to focus on the need for new capacity and the potential to expand revenue and market share — even if such moves mean potentially sacrificing margins and reducing yield.

This year’s Airline Economic Analysis reinforces earlier findings that adding capacity at a pace faster than US economic growth has contributed to carriers’ eroding margins over the past several years. This is a situation likely to continue until a balance between supply and demand is restored.

- Even as oil and jet fuel prices decline, airline margins drop.

- Oliver Wyman In 2014, capacity began to expand faster than the US gross domestic product (GDP) — much faster, in fact.

- That year, GDP grew 2.5 percent versus capacity growth well above three percent.

- By 2015, capacity growth was peaking above four percent, while GDP was 2.9 percent.

Industry margins reached 15 percent, helped by oil prices that averaged around $50 a barrel. GDP took a sudden slide in 2016 to below two percent as the trade deficit ballooned and oil prices plunged. While airline capacity growth also began to slow, it failed to match the drop in GDP.

- That’s when margins began to fall, despite lower oil prices.

- Even with cheaper oil In January 2016, prices per barrel slid to around $35 from a high of more than $110 in 2014.

- Although prices quickly recovered to above $50, they have not returned to the $80-plus levels they had maintained between mid-2009 and October 2014.

While fuel typically makes up between 25 and 30 percent of total operating costs for carriers and represents the industry’s second-largest expense, the pattern of margin decline makes it clear that many factors other than fuel — most notably labor, the No.1 expense, and capacity — affect profitability as much or more over the medium to long term.

One caveat: While margins have tightened since 2015, they are still higher than they were from 2010 to 2013, when they were six percent or lower and oil prices were consistently above $80. The fact that margins were in the teens from 2015 to 2017, even though on the decline, reflects the impact of lower oil prices.

While airlines remain profitable, the prospect of slowing GDP may force carriers to reassess capacity expansions, especially given rising pressures on operations from that rapid growth. Indeed, the industry’s biggest risk over the next decade may be failing to strike the right balance between capacity and profitability at a time when managing operations grows increasingly difficult.

- Oliver Wyman’s Grant Alport, Andy Buchanan, and Aaron Taylor contributed to the research and insights in the 2019 Airline Economic Analysis and in this article.

- Grant is a principal, based in Washington DC, in the transportation practice.

- Andy is a vice president, based in Chicago, in the transportation practice.

Aaron is a senior manager in the transportation practice who handles Oliver Wyman’s aviation business intelligence offering, : Margins Are Tightening For US Airlines As Capacity Growth Keeps Outpacing GDP